In 2010 one of the graduate students in my Critical/Performance Ethnography course asked me if I would talk about how my research on Portobelo was a work of “critical ethnography.” The question was a fair and anticipated one. In my initial response, I talked about the ways in which I coupled critical theory with embodied field research, paid close attention to the workings of power and the circuits through which the community and I variously engaged it, and attempted to intervene in the representational politics of the area, which often frame Congo performance as narrowly folkloric and social in a way that flattens its sociopolitical history and the nuances of its contemporary practice.

As a critical/performance ethnographer, I have consistently used live performance and performance-installation projects as a means to make my research more accessible, especially to the communities reflected by and invested in its outcomes. Doing so has made the research significantly stronger. Although my work serves the Congo community of Portobelo, Panama, by addressing an absence in scholarship about their cultural contributions to the development of the Republic and the cultural history of the Americas, I felt exposed by my student’s question because I knew that my work did not yet effectively respond to a call from the community for a specific type of critical intervention—cultural preservation that might be more accessible and usable within the community.

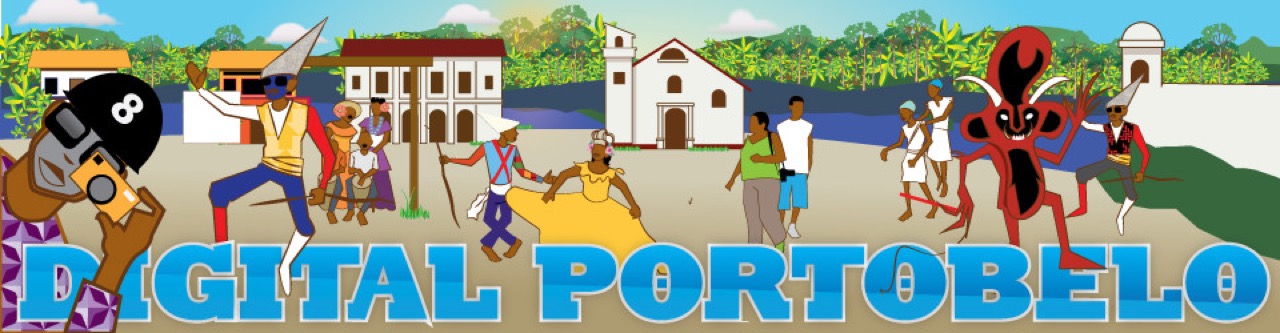

For years, I had shared my photographs and recordings on a small scale with local families, but that did not effectively contribute to a communitywide cultural preservation initiative. Originally, the idea of how I might do that baffled me and far exceeded my skills and resources. By the time the student posed the question to me, however, user-friendly, open-source digital tools and greater support—in the form of monetary resources, trained personnel, and expanding digital infrastructures within my home institution as well as in Portobelo—made more plausible the possibility of responding to the community’s call through a digital intervention. So, instead of merely responding to the student’s question based on where I thought the project succeeded as a work of critical/performance ethnography, I decided to talk about the horizon of possibility still open for it and how I hoped to help it to explore that horizon. In doing so, I imagined aloud, for the first time, the broad strokes of what would become Digital Portobelo: Art + Scholarship + Cultural Preservation.

Excerpted from “Epilogue,” When the Devil Knocks: The Congo Tradition and the Politics of Blackness in 20th Century Panama, The Ohio State University Press (January 2015).