In January 2013, I lined up over a decade’s worth of Hi8, VHS, VHSC, mini DV, and audio cassette tapes from my research in Portobelo, Panama, to digitize them. The process left me feeling both liberated and nostalgic. For my work, this first step toward “becoming digital” meant trading fat and skinny material objects with texture and weight for something “other” “elsewhere”—translating present, tangible objects that live in my home into distant, hyperlinked files that live on servers and external hard drives. As plastic objects, these meaning-filled coils of qualitative “data” are limited to their containers and to my ability to access them. Translated into a universal language of zeros and ones, they offer the possibility to reach out as well as reach back—to create new networks through which the research may more easily connect with intimate community knowledge and other research in order to round out our collective view of Portobelo’s past and nuance the questions we are able to ask in the future.

Expanding my performance-centered work to critically incorporate digital tools and methods has given me a way to work collaboratively with the Portobelo community to address its need to better preserve its culture while advancing scholarship about it. As a powerful complement to my critical/performance ethnographic work, digital technologies have the potential to 1) expand opportunities for dynamic, sustainable, mutually beneficial collaborations across geographic locations; 2) narrow the ideological space between researchers and the communities within which we work, especially when we return “home” from “the field”; and 3) lower barriers to access by providing open-source, user-friendly platforms that allow for more organic co-creation, critique, and consumption.

Likewise, approaching the digital humanities with tools, methods, and analytics gleaned from my location as a performance-centered critical ethnographer opens the potential to 1) challenge and expand notions of “open-access”; 2) critically engage with digital tools and the products we make of them as nonneutral cultural artifacts that circulate within plural cultural and political economies often unwrapped from the careful contexts in which we bundle them; 3) create partnerships between computer scientists, humanities scholars, web designers, program developers, and community members to analyze the ways in which some existing digital rubrics sometimes flatten the complexity of qualitative research through the translations necessary to make the work legible within more quantitative computational systems; and 4) explore those existing limits as productive challenges that might simultaneously “grow” the technology as well as lead qualitative researchers to be more explicit about the systems of coding and categorization that guide the analytical work of our projects. In order words, working together to “teach” digital tools how to organize and render our projects with the complexity we intend demands that we critically examine and explain the micro-steps we use to make the material mean and matter in the particular ways they do in our written and embodied scholarship.

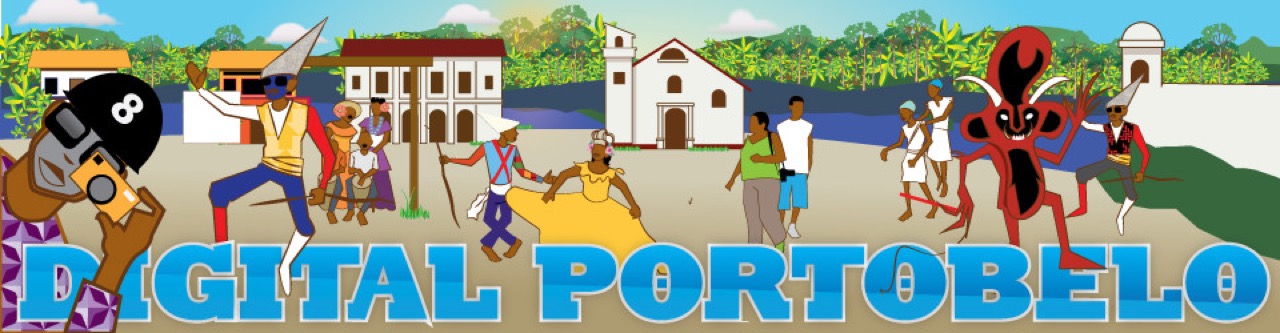

Over the past year, I’ve had conversations in two countries, toggling between a smartphone texting program called WhatsApp, Facebook, Tumblr, Twitter, and two email accounts in order to meet, plan, and strategize with team members in Atlanta, Georgia; Los Angeles, California; Hillsborough, North Carolina; Durham, North Carolina; and Portobelo, Panama. Digital technologies are a valuable part of my current critical ethnographic toolkit. These virtual opportunities in no way stand in for the persistent need for sustained face-to-face community engagement. However, prior to these technological advances, the gaps between in-person visits were largely filled with short, expensive telephone calls to celebrate or mourn a milestone. Now, the time in between visits is filled with active collaborations and the type of sustained, informal interpersonal contact that enriches our abilities to build meaningful relationships. That said, the global digital divide is deep and wide, especially between rural and urban areas, not to mention the Global North and the Global South. It is not just a question of access but of the quality, speed, cost, and reliability of that access. What new possibilities abound in engaging the products and processes of research through digital technologies? What new frictions arise at the multiple levels of translation when textured, fragmented surfaces can be rendered seemingly smoother? What “back stage” labor, infrastructure, resources, and proficiencies are needed to make the “front stage” visible, navigable, and engaging? What resources, technologies, and proficiencies serve as the “price” of admission? And, through what processes, using which mediums, can that “price” be significantly mitigated? Digital Portobelo aspires to serve as a public platform that might allow researchers and community members to address these questions and find answers together.

Excerpted from “Epilogue,” When the Devil Knocks: The Congo Tradition and the Politics of Blackness in 20th Century Panama, The Ohio State University Press. (in press)