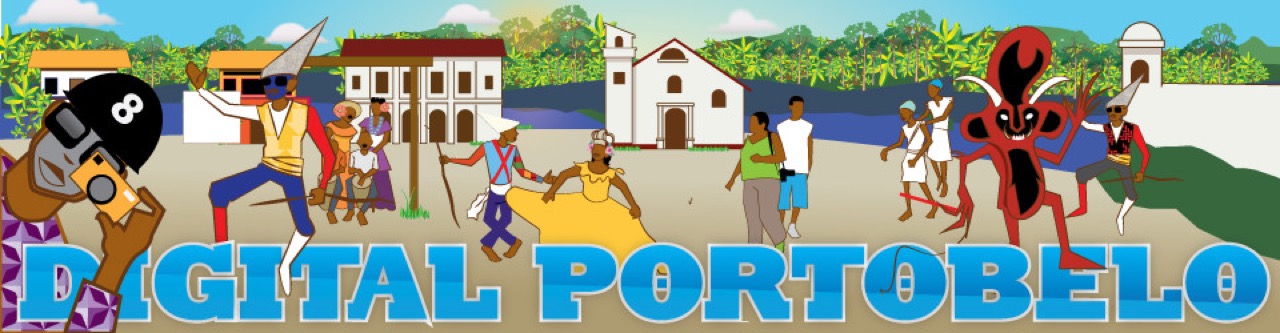

Speaking in Congo (Photo by Elaine Eversley)

Language was one of the primary means through which enslaved people subverted Spanish colonial rule and Cimarrones enacted community and culture. It remains one of the most political and dynamic elements of Congo culture. The “Congo dialect” is a coded intra-group lexicon that successive generations of Congo practitioners have used to exercise resistance while appearing complicit. It emerged as a part of the culture of enslaved people in Panama just as “Negro” spirituals served as a coded message system among enslaved people in the United States. Unlike spirituals, however, which have maintained their racial and historical specificity but are no longer used as code, the Congo language maintains its multiplicity. Speaking “Congo” is not only a way of organizing knowledge about the world but also a way of thinking about the self and the world. Further, it offers a means to “trick back” on systems of power over which Congo practitioners may have little control.

Frantz Fanon (1967) theorized that language was one of the key areas that created psychosis among Blacks (17). “To speak,” he said, “is to exist absolutely for the other.” We think and exist in the structures of the languages we speak. “A man who has a language,” Fanon suggests, “consequently possesses the world expressed and implied by that language” (18). He goes on to say that “every dialect is a way of thinking” (25). African slaves combated this “psychosis” by creating a creolized, secret language strategically couched in the dominant discourse. Contemporary Congo communities continue to follow this model.

In order to give an example of the contemporary political currency of Congo speech, the Taller Portobelo co-founder, visual artist, and Congo ritual specialist Yaneca Esquina shared an anecdote with me during our May 2000 interview about the time he and other Congo members were asked to perform before Panama’s former military dictator, Manuel Noriega. Understandably, they could not refuse. According to Yaneca, everyone called Noriega “pineapple face” behind his back, so the Congos called him “pineapple face” in coded language as they sang and danced in front of him. Speaking in Congo allowed the practitioners to simultaneously comply with a request they could not refuse and subvert the request by saying the unsayable. In the language of James Scott’s (1990) well-noted schema, the Congo dialect allowed the community to express a “public transcript” that aligned with their host’s expectations while enacting a “hidden transcript” that expressed their contempt. Noriega formed part of the extended group of “outsiders” who were unwittingly part of the joke, while the small group of Congo performers and those community members assembled to support them served as “insiders” who understood the layered performance and got the joke.

Unlike the women, the King and Congo men paint their faces with charcoal or indigo and wear both trousers and a long-sleeved shirt or jacket turned inside out. Recounting a memory of watching her father get dressed as the Congo King, Simona Esquina shared:

All of my life, from the time I peeled opened my eyes, [my father] was Juan de Dios of the Congos. He was the King of the Congos. His Congo name was Juan de Dios but his birth name was Vicente Esquina. I would see him dress as a Congo with his clothes and rope [belt], lots of banana leaves tied on. [. . .] His crown and face painted blue-black. [. . .] then you put on black circles and your red lips. [. . .] He would use charcoal. [. . .] But first he would put on the blue [indigo]. He would get a little bit of water. He would paint his whole face with that, then he would put on black circles with charcoal, and I would watch him as a child. When I would see him painting his face I would ask him, daddy, where are you going? He would say, daughter, I’m going to Congo. [. . .] I’m going to Congo because I’m Juan de Dios and I have to be there together with my women. So then as a child I would go. I would see them dancing Congo and that’s how I began. [. . .] I enjoyed it.

Male Congo practitioners’ costumes also include a cone-shaped hat. Whereas the contemporary Congo hat is formed by layers of papier-mâché and adorned with mirrors, beads, and feathers, Simona explained that the traditional Congo hat was made from foliage: “Normally, here, the Congo hat has been the kafucula. The kafucula is the leaf of a coconut tree. That’s the original Congo hat. The Congo adorns the kafucula—he puts on his decorations, feathers, and colorful objects. So the kafucula is the hat, but Congos from other places use whatever [kind of hat, and that is outside the norm].” Expanding upon the Congo costume, she said:

The outfit of the Congos of Portobelo is very different from the outfit of the Congos of Colón, Costa Abajo, and Panama [city]. The Congo here dresses very distinctly. [. . .] There, the Congos dress using lots of bits of torn pieces of fabrics. [. . .] Yes, they all dress like that. In Colón and Panama City, the Congos dress like that. Everybody with little bits of torn fabric. But not here. Here, the Congos don’t dress like that. When you see a Congo here dressed with those pieces of torn fabric, you know that he’s not from Portobelo. He’s not from Costa Arriba.

Each Congo man carries a satchel over his shoulder to collect provisions and wears a belt of artifacts (plastic flashlights, coconut shells, plastic dolls) tied around his waist with a rope. Like the women, men wear layers of long beaded necklaces and stylize their costumes according to taste. During the 2003 Centennial, for example, a Congo elder made part of her pollera from a large Panamanian flag while Congo artists like Yaneca Esquina (pictured above) and his son Gustavo speckled their jackets and pants with paint in the pointillist style of their Congo paintings.

According to Melba Esquina, “As the Black was treated like an animal, they gave themselves animal names [for the Congo drama]: Rabbit, Sparrow-Hawk, Small Tiger, etc.” When I spoke with him, Carlos Chavarría elaborated:

The Congos would use purely animal names for themselves, for example, Ocelot, Fox, Pig, Rabbit. [. . .] Some would use names like Doctor, others [would use] Lawyer, but that was really unusual because most people used strictly animal names, and only occasionally used names of professions, right? But when they did you would see them with a book. If they were a lawyer, they used a book [as a prop]. If an Engineer, you would see them with their tape measure. If they were a doctor, they’d have a stethoscope. They may be presenting as that, but they were always imitating. [. . .] But if you were going to be seen as that, it was something you lived.

Throughout Carnival season Congo male practitioners alternate between drumming, dancing, and engaging in buffoonery as a tactic of subversion, misdirection, and evasion.

Excerpted from “Chapter Two,” When the Devil Knocks: The Congo Tradition and the Politics of Blackness in 20th Century Panama, The Ohio State University Press (in press)