- Preparing for Local Tourist Presentation

- Congo Performer and Visual Artist Yaneca Esquina

- Performing at Local Event

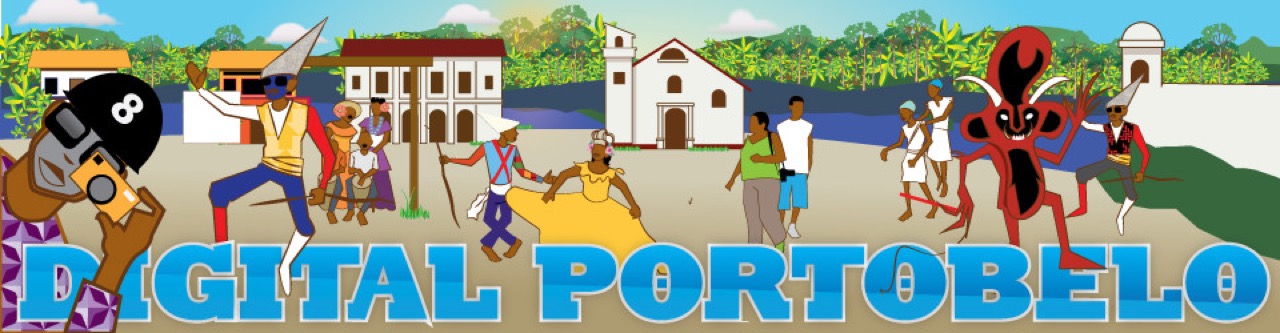

Congo Carnival traditions in Panama celebrate the resistance of Cimarrones, formerly enslaved Africans during the Spanish colonial period who escaped to the hills and rain forests of the Americas to establish independent communities.[i] Los Cimarrones assisted English privateers like Francis Drake and pirates like Henry Morgan to successfully sabotage Spanish colonial trade practices. Using these partnerships as leverage, the Cimarrones were able to negotiate with the Spanish to gain their freedom.[ii] Once successful, they were no longer “Cimarrones,” meaning “wild” or “runaways.” They were free Blacks, free “Congos.” Origin narratives surrounding the name “Congo” suggest that it originally functioned as a generic nomenclature, similar to “Negro,” that Spanish colonists used to refer to Africans and their descendants, and that a significant number of enslaved people initially might have been transplanted from the former Kongo kingdoms of Central and Western Africa.[iii] While “Congo” was once an explicit ethnoracial term, contemporary practitioners use it to mark a cultural performance traditionally enacted by Afro-Colonial communities as a celebration of their history and culture in Panama. “Playing Congo”[iv] allows practitioners to celebrate and share their history and traditions through a set of ritual performances nested within larger cultural ones.[v] The main drama of the Congo tradition takes place on the Tuesday and Wednesday before the beginning of Lent, the forty days from Ash Wednesday until Easter.[vi]

- Congo Chorus and Drummers

- Congo Performer and Visual Artist Ariel Jimenez

The Congo drama is a mythic battle between good and evil. Architects of the tradition cast the Congos/Blacks on the side of the good and the Devil/brutal enslavers on the side of evil. As Michel de Certeau (1984) argues regarding the agency of people living in subjugated conditions, “without leaving the place where he has no choice but to live and which lays down its law on him, [the subjugated person] establishes within it a degree of plurality and creativity. By an art of being between, he draws unexpected results from his situation” (30). On July 10, 2013, I interviewed Carlos Chavarría, who “plays Congo” as the Major Devil. He epitomized the drama this way: “For us, the Congo tradition is a culture. It was born during the Colonial times with the arrival of Black slaves from Africa to Panama, to the American continent. And, mainly, they were first unloaded in Portobelo as slaves.” Like most Carnival traditions throughout the Americas, Congo traditions in Panama rely on a hierarchy of characters. The primary characters include Merced (the Queen),[vii] Juan de Dioso (the King), Pajarito (the Prince, whose name means “little bird”), Menina (the Princess), Diablo Mayor (the Major Devil), Diablo Segundo (the Secondary Devil), a host of minor Devils, a Priest, one Angel and six souls, a Cantalante or revellín (primary singer), a female chorus, three male drummers, and a multitude of male and female Congo dancers. Through the Congo drama and the language of the Congo dialect, the characters parody the Catholic Church and the Spanish Crown to create an embodied critique of the institution of slavery and its primary agents. Parody, manifested in reversals of meaning as well as reversals of clothing, is a central element of the drama. Spanish colonialists appropriated the Christian devil as a weapon to wield against enslaved communities. Oral history suggests that they sometimes used the threat “The devil will get you” to dissuade rebellion and discourage escape. Congo practitioners recognized their enslavers as the embodiment of that threat and repurposed the trope of “devil” as parody. In doing so, they created a narrative that casts enslavers as whip-wielding Devils to be captured, baptized, and sold by communities of self-liberated Blacks powerful enough to do so. They created a narrative that celebrated the history and spirit of cimarronaje—of self-determination, resistance to enslavement, communalism, and freedom. The Congo drama, also referred to locally as “the Congo game,” does not end until the main Devil, El Diablo Mayor, is de-masked, de-whipped, baptized, and symbolically sold. The ethos of Black rebellion, resistance, and reappropriation, which frames Panamanian Congo traditions in global imaginaries, stems from the cultural context of playing with the devil and winning.

- Archangel and Ánimas

- Congos Posing After Tourist Presentation

Excerpted from “Prologue” and “Chapter Two” of When the Devil Knocks: The Congo Tradition and the Politics of Blackness in 20th Century Panama, The Ohio State University Press (January 2015)