Introduction

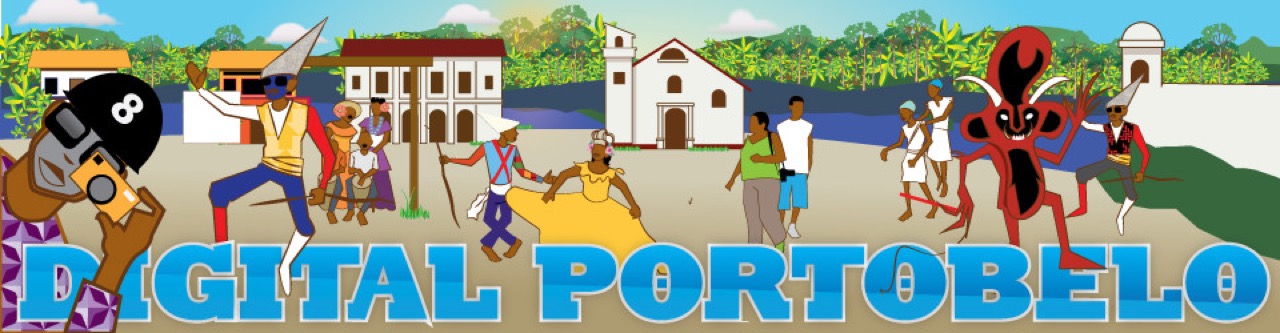

There is an everyday magical quality about experiencing contemporary Portobelo for the first time. It is a thriving contemporary town growing between the carcasses of two colonial forts – a community of colorful cinderblock houses planted in the middle of a bayside rainforest. It is a colonial church with a five-hundred-year-old Jesus as brown or browner than most of the townspeople and a custom’s house that protected Spanish gold against pirates and privateers in its youth and now tells its story to visitors like an elder statesman. This, of course, is a cursory view—like climbing to the top of El Mirador, the lookout high above the city, and looking down. The view from below is that of a townscape soaked in salt water, rained on, and slightly faded by the sun. Clothes, like dishes, are generally washed by hand and put out to dry without the luxury of hot water. Mildew marks humid concrete walls and rust flourishes on pie-pan roofs. Homelessness is non-existent but hunger is not, despite a fertile rainforest and generous turquoise sea. During the four months of summer, faucets dry up as dead frogs contaminate the aqueducts and amoebas pollute the belly. Alcohol is cheap, abundant, and free of unexpected pollutants. It anesthetizes against both boredom and despair. This is the view from the bottom. Both the “storied” historical and “lived” contemporary views lie somewhere in-between the mountain and the ground.

Excerpted from “Introduction,” When the Devil Knocks: The Congo Tradition and the Politics of Blackness in 20th Century Panama, The Ohio State University Press. (January 2015)