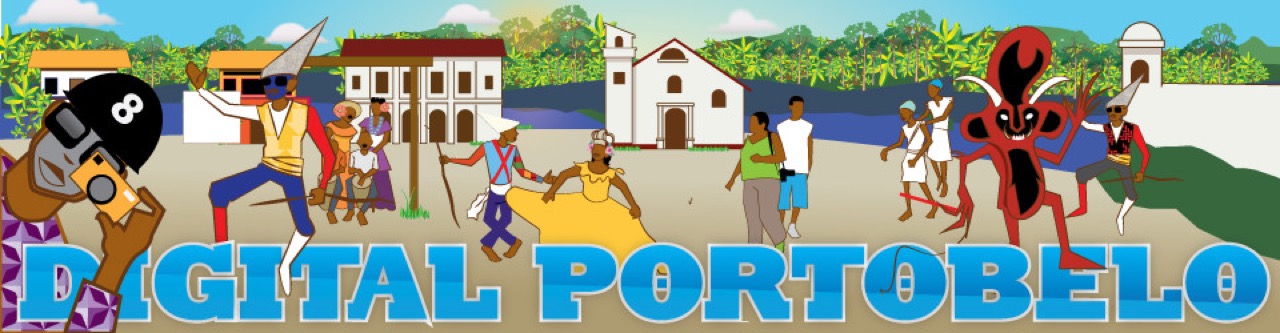

Congo Chorus and Drummers (Photo by Renee Alexander Craft)

In addition to the Congo royal court and supernatural characters, the heart of the tradition is Congo dance, which is animated by the percussive pulse of three male drummers led by a female chorus and a primary singer. In her book entitled Paloma, reina de los Congos: El orgullo de una raza, the Congo specialist Maricel Martín Zuñigan (2002) states:

The “cantalantes” are the key to the Congo because in order to have a good Congo dance it is very important to have a good cantadora. [. . .] These women also are given their Congo name that differs and sometimes in groups are often called “Re[v]ellín” and “Cicada” because they have a privileged voice for this [type of] song. There are also other women who are responsible for composing songs. (6)

Melba Esquina explained that the Congo percussion section “is composed of three drums: El hondo, el bajo, and el requinto; the lead singer and the chorus that with hand clapping raises the rhythm of the drums.” Simona also described the music: “The Blacks, the Black Africans, they created their own drums. They created their own music themselves, and from there the Congo woman created the waist movement, because the Congo [dance] is a waist movement. Yes, and they created their dance themselves. Yes, they created their dance.”

From January 20 through the season’s culmination, this constellation of dancers, singers, and drummers form the tradition’s foundation. During Carnival season, they gather to fellowship, play, and celebrate with one another each Friday and/or Saturday night as well as from dusk on Carnival Tuesday through the end of Carnival on Ash Wednesday.

Outside of its Carnival context, Congo social dance may be performed informally in a cantina, backyard, or wherever an improvised drumbeat or bass line inspires it. According to Melba Esquina, “A Congo woman lead[s] the dance with her hip movements to invite the Congo men to dance. In the dance, he makes all types of faces and advances toward her trying to kiss her and she, with her skirt, tries to cover herself and is always shaking her skirt. It is a tease. Another female dancer replaces her and the dance continues and so on and so on for both sexes.” When this social dance element includes the Congo drummers, chorus and revellín, it is referred to as a congada, meaning “mini Congo performance.” Each Friday and Saturday evening from January 20 until Lent, Congo communities throughout Panama hold congadas. This interplay between the drummers, singers, and dancers forms the foundation of all Congo performance, including Congo ritual performance, parts of which date back to Panama’s Spanish colonial period.

Excerpted from “Chapter Two,” When the Devil Knocks: The Congo Tradition and the Politics of Blackness in 20th Century Panama, The Ohio State University Press (in press)