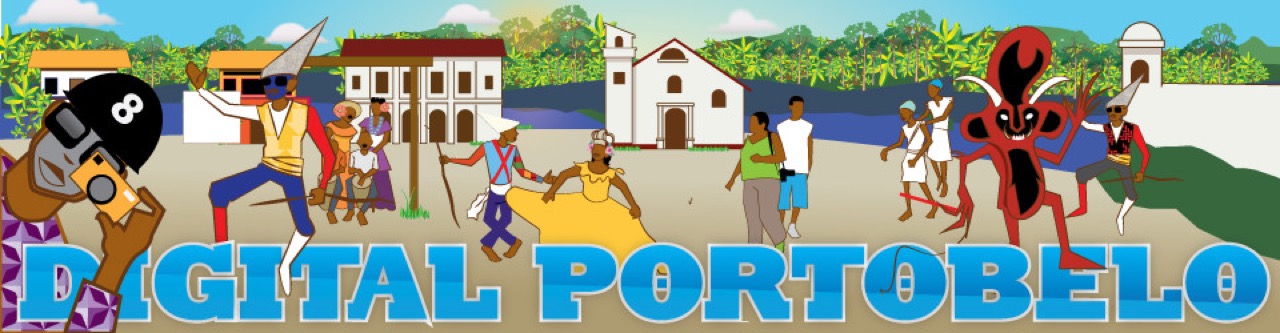

What is Digital Portobelo?

Digital Portobelo is an interactive online collection of ethnographic interviews, photos, documentaries, short videos, artwork, and archival material illuminating the rich culture and history of Portobelo, Panama. Portobelo is a small, rural community located on the Caribbean coast of the Republic of Panama best known for its Spanish colonial heritage, its centuries-old Black Christ festival, and an Afro-Latin community who call themselves and their carnival performance tradition “Congo.” Digital Portobelo seeks to make research about the Congo tradition and the town of Portobelo more available and accessible beyond the academy.

When did this project begin?

Renée Alexander Craft alongside collaborators in the US and Panama launched the first version of Digital Portobelo in 2013 as an extension of ethnographic research in Portobelo, Panama, which she began in 2000. In addition to this community-engaged digital humanities project, she has published a monograph that reflects the research titled When The Devil Knocks: The Congo Tradition and the Politics of Blackness in Twentieth-Century Panama.

Where did the “Congo” community of Portobelo come from?

Portobelo was founded on March 20, 1597 after Nombre de Dios, the site of Panama’s first Atlantic-coast Spanish settlement, was looted and sacked by the privateer Sir Francis Drake. The Afro-Latin community of Portobelo who celebrate “Congo carnival” and call themselves “Congos” today are culturally descended from “Cimarrones” — formerly enslaved people who liberated themselves and escaped to the hills and rainforests. Two accounts of the relationship between arriving Spaniards and Cimarrones persist in local oral history. For more information on this relationship between Spaniards and Cimarrones, check the Historical “Storied” View page of our About Portobelo, Panama section.

Is the Congo carnival tradition symbolic, religious, or both?

Congo carnival engages with religious themes and symbols, but it is a cultural performance rather than a religious one. Carnival traditions were introduced to Panama by Spanish colonists and included pageants and performances that reflected Spain’s Roman Catholic heritage. Carnival season refers to the period right before Lent, the forty days between Ash Wednesday and Easter or “Resurrection Sunday.” Carnival season is the period of celebration, excess, and indulgence before the Lenten period of quiet reflection, moderation, and self-control. Various ethnic communities in Panama adapted Spanish colonial carnival practices to represent their unique experiences, aesthetics, and interests. Congo carnival includes characters and symbolism from the continent of Africa, which enslaved people brought with them in their memories, stories, and tradition; as well as characters and symbolism from European practices of carnival, which included Catholic religious symbolism. The celebration is not a religious event, but the story it tells includes religious elements.

Congo carnival is a cultural practice that emerged as a performative response to enslavement in Panama. Congo carnival traditions in Panama celebrate the resistance of Cimarrones, formerly enslaved Africans during the Spanish colonial period who escaped to the hills and rain forests of the Americas to establish independent communities.

The main drama of the tradition takes place during carnival season, which peaks on the Tuesday and Wednesday before the beginning of Lent. The Congo drama is a mythic battle between good and evil, which pits Congos — self-liberated free Blacks — against devils — brutal enslavers. Like most carnival traditions throughout the Americas, Congo traditions in Panamá rely on a hierarchy of characters. The primary characters include Merced (the Queen), Juan de Dioso (the King), Pajarito (the Prince whose name means “Little Bird”), Minina (the Princess), Diablo Mayor (the Major Devil), Diablo Segundo (the Secondary Devil), a host of minor devils, a priest, one angel and six souls. Enslavers appropriated “the devil” and “the church” as a means to dissuade rebellion and protect the institution of slavery. The Congo game reappropriates power such that the Congo Queen uses her cross/the church to combat the Devil/enslaver for the protection of her nation. To learn more about the Congo tradition, visit the Congo Carnival page on our sister site Picturing Portobelo.

Does everyone in Portobelo, Panama participate in the Congo tradition?

Not everyone living in Portobelo practices the tradition. Taking part in it is done out of choice and desire to engage with the community. Generally, the primary Congo practitioners are from families with long generational roots in Portobelo. However, those who embrace the story of Black struggle and triumph that the tradition honors may also be welcomed into leadership roles over time. Many residents who do not have official roles in the tradition enjoy watching and participating in it as observers.

For more information about community participation in the Congo tradition, please feel free to explore Digital Portobelo’s interviews through our Interactive Project, available in Gallery or Concept Map views.

How can I engage with Digital Portobelo on other platforms?

Digital Portobelo has extended its presence to a variety of social media platforms.

SoundCloud: https://soundcloud.com/digitalportobelo

Follow us on SoundCloud to access our archive of interviews with the people of Portobelo.

YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/user/digitalportobelo

Subscribe to Digital Portobelo on YouTube to access an archive of documentaries about Portobelo and video tutorials for the site.

FaceBook: www.facebook.com/digitalportobelo

Like us on FaceBook to see updates on this ever-evolving digital humanities project.

Instagram: #digitalportobelo; follow us: @digitalportobelo

Follow us on Instagram and keep up with our hashtag.

Twitter: #digitalportobelo; follow us: @digitalpbelo

Follow us on Twitter and keep up with our hashtag.